Hella Hammid was the first civil person to work with Russell Targ and Dr. Harold E. “Hal” Puthoff. The great successes at SRI with Ingo Swann and Pat Price prompted government contractors to order researchers to find “completely normal” people – who were not paranormal from birth and have no PSI experience – and work with them as control persons.

The first remote viewer who was a “normal person”

The history and achievements of Hella Hammid have essentially paved the way for the realization that PSI perception (and thus also remote viewing) is an inherent human ability.

Hella Hammid was a long-time friend of Russell Targ from New York times, who had “looked at the world through the scope of a Leica” for most of her life. She had made a name for herself as a photographer, and now she was excited about the challenge of coming to the SRI as a “control person” to answer the question of what a normal person could do in the PSI area. Hella came with no previous experience in matters of PSI and ESP (extrasensory perception), and certainly would not have imagined herself that her involvement in this would end up lasting eight whole years. The remote viewing episode in Hella Hammids Leben was intense and full of surprises, not least for herself. In 1982 Hella left Hammid the SRI with Russell Targ and then turned back to her photography with great success in Los Angeles.

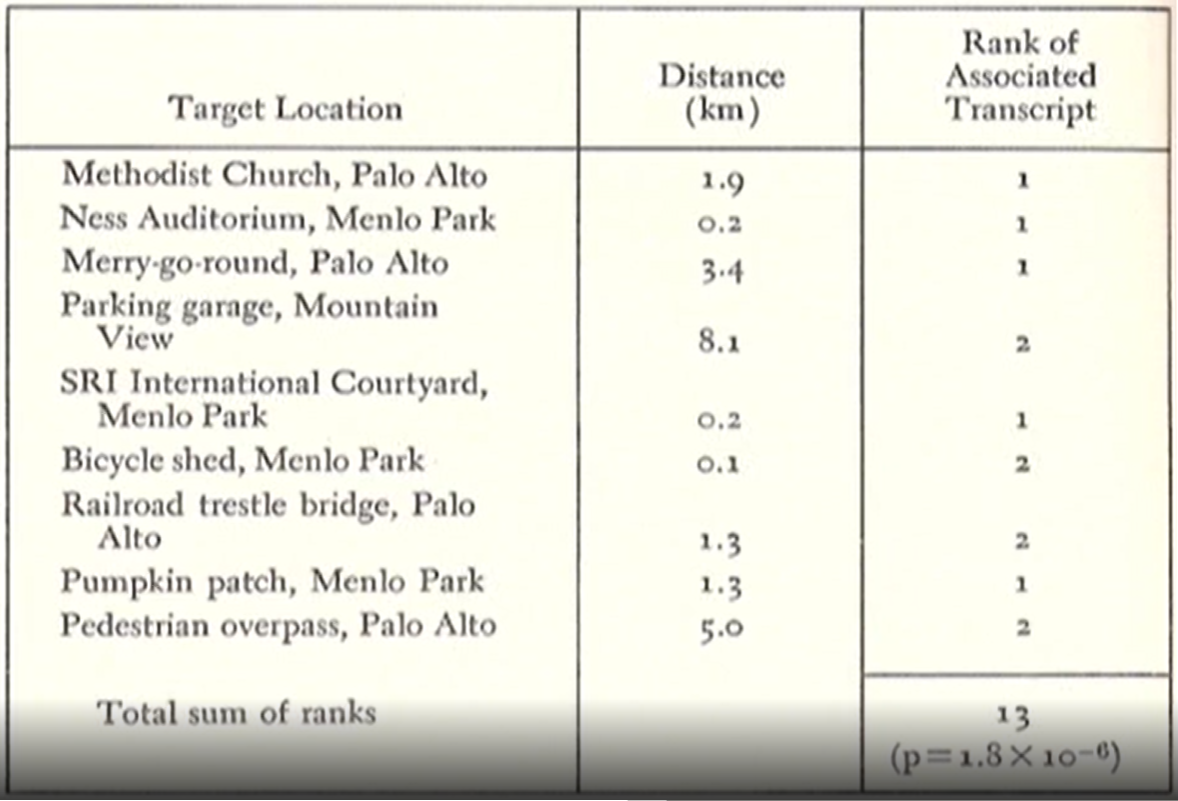

Hella was very popular at SRI because she was a very warm and charming person. To everyone’s surprise, she became the most reliable remote viewer at the institute. Her skill and accuracy exceeded even Pat Price’s by 10 times. In her nine attempts to perceive distant geographic targets, she achieved a statistically significant probability of close to one in a million (1.8 x 10 -6) that their impressions may have occurred by chance. Both her and Pat Price’s results were reported in the Proceedings of the IEEE published March 1976. This in turn encouraged other scientists to successfully repeat the series of experiments internationally (including Princeton University, universities in Russia, Holland and Scotland). There were a total of fifteen successful repetitions of the series of experiments by 1982.

In a report from September 1979, (written by the “AMSAA Grill-Flame Core Group”, Skip Atwater, Mel Riley, McMoneagle and Manfred Gale), Hella Hammid and her way of working are discussed in particular.

Hella Heyman Hammid (1921-1992)

Portrait of Hella Heyman from her personal file at Black Mountain College, 1940.

(Courtesy of the Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina)

Hella was a German-American photographer who taught at UCLA, among other places. She was born in Kronberg im Taunus (near Frankfurt / Main, Germany) as Hella Hilde Heyman and emigrated to the USA in 1937/38 due to her Jewish roots. First she lived in New York City, later in Los Angeles. Her mother was already a photographer, and because Hella always helped her, she was able to acquire the craft from scratch. In California, she assisted painter and art dealer Galka E. Scheyer with classes and exhibitions. Ms. Scheyer also helped her with a reference, at the “Black Mountain College”. Last but not least, these two building blocks laid the foundation for her later artistic-photographic work. It was also Galka Scheyer who, with her letter of recommendation, secured Hella an acceptance at Black Mountain College (North Carolina). Unfortunately, for financial reasons, she was unable to finish her studies there, but returned to NYC, where she assisted on film sets and established herself as a freelance photographer and writer.

Her photographs have appeared in various publications such as Life, Ebony, The Sun and The New York Times. One of her photos was shown at MoMA (in the influential exhibition “The Family of Man”, 1955).

Heyman married the director and cameraman Alexander Hammid ( Alexandr Hackenschmied) after his divorce from Maya Deren in 1948. She had met him while working on a film together. The pair had two children and the family lived in Upper Manhattan, NYC, most of the time. Hella died on May 1, 1992.

Hella Hammid, Bathing, 1988, vintage gelatin silver print. Private collection.

Remote viewing from Hella Hammid

Hella Hammid’s first remote viewing with Hal Puthoff as outbounder: A pedestrian crossing in the Bay Area. (Courtesy of Russell Targ)

Hella’s very first session was a success, which her colleague Russell Targ likes to cite as an example to this day because of its visual conciseness.

In this context, Targ, who was the interviewer of Hella (and also of the other viewers) at that time, describes that he thinks it is especially important which words one chooses to ask the viewer about his impressions. The method at the time was based on the so-called outbounder experiments, in which a person was staying at a randomly selected location in the Bay Area while the viewer was asked to describe his whereabouts at the same time. He was asked about this by an “interviewer”. This so-called “Generic Remote Viewing” – as it was called retrospectively – was the basic working method of the viewers in all SRI experiments in this first decade of remote viewing history.

Hella’s red leather doors in the Kremlin, in the description of Brezhnev’s study, 1981 (verified 1983).

In his lecture “A Tribute to Hella Hammid: The First Woman Remote Viewer”, which he gave together with Stephan Schwartz at the 2009 IRVA conference, and in the documentary “Third Eye Spies”, Russell Targ shows some interesting examples of her work.

Among other things, her psychic “visit” to Leonid Brezhnev’s office in the Kremlin, a target that she was officially given in 1981, was impressive. Hella described a red leather door with upholstery nails, then a large desk on the right, window on the left, and a door in the wall behind the desk. When Targ was invited to visit by Moscow three years later, he had the opportunity to see this place live and found everything to be exactly as described by Hella. Only the secret underground computer room, which she had also described, could of course not be entered by Russell.

––– Remote viewing with lucky socks

One of the charming stories surrounding Hella is that, like Pat Price, she had a little ritual when she went to an RV session. He cleaned his glasses every time – and Hella put on her “lucky socks”, with an eye on each of the two big toes … so that she could “see” better.

From Deep Quest to the Alexandria Project

The records and evaluations of that time show the fundamental questions research had to investigate first. Many things that we take for granted today were by no means back then. For example, the table for the first place matches from Hella’s first series of 9 lists the distance of each target location. At that time it was not yet known whether and in what way PSI signals were being transmitted, and their dependency on the distance as well as on the shielding was investigated. Consider how daring or crazy Ingo Swann’s view of Jupiter from April 1973 must have appeared against this background.

The records and evaluations of that time show the fundamental questions research had to investigate first. Many things that we take for granted today were by no means back then. For example, the table for the first place matches from Hella’s first series of 9 lists the distance of each target location. At that time it was not yet known whether and in what way PSI signals were being transmitted, and their dependency on the distance as well as on the shielding was investigated. Consider how daring or crazy Ingo Swann’s view of Jupiter from April 1973 must have appeared against this background.

At some point almost all electromagnetic spectra had been excluded as carriers and only the ELF waves remained. To check this, one would have to stay in a submarine far below sea level, it was said. So in the spring of 1977 the well-known “Deep Quest” experiment was carried out in collaboration with Stephen A. Schwartz. For this experiment, Hella overcame her displeasure towards ships and boats and went on board. Three different questions were examined simultaneously during the dive: Do the ELF waves have an impact on RV? Can ARV technology be used for communication on ships and submarines? Is it possible to locate an unknown wreck on the ocean floor?

The very first ARV session in the world took place on board the submarine.

––– The birth of ARV

When Hella Hammid was asked if she wanted to take part in the submarine experiment, her first answer was: “I really don’t like boats.” Nonetheless, she overcame herself and got in. Hella and Ingo were each to perform 4 dives with the Taurus I, to a depth of 170 m. The experimental setup was based on the already known outbounder experiments. From the submarine, at a predetermined time, the viewers had to describe the whereabouts of Puthoff and Targ, which, as always, were randomly determined from a selection of 6 locations in the Bay Area.

Schwartz, who had organized the submarine experiment since the fall of 1976, introduced an additional question: could this form of remote viewing be used as a form of communication with submarines? What if each of the possible targets was linked to a message? For example, a large fountain in the target pool might stand for the command “surface for radio contact”; if the target was a swimming pool, the message might instead be “hide under the polar ice and await further instructions”. Hal Puthoff and Dale Graff had already considered such a communication concept independently, so they helped develop the message/target set. A list of 6 targets and the messages assigned to each for the submarine was sealed and not given to the viewer until after the session. He should now determine which of the six places he had best described with his view. The message on the back of the chosen target was then the action instruction for the submarine captain. This was the birth of what would later become known as ARV – or “Associative Remote Viewing”.

The target of the first ARV session: Hal Puthoff climbs into the crown of a large oak tree.

Hammid started the series of experiments. The small submarine sank to a depth of 170 m or over 550 ft below sea level. Below the boat there was another 500 ft of water to the sea floor. This position was calculated to achieve maximum shielding of ELF waves, whose possible involvement as a transmission medium was a priority to investigate. Hella Hammid got seasick during this passage because the small submarine rocked violently on the surface before it went diving. Nevertheless, she mustered all concentration and at the predetermined time viewed the location where Puthoff and Targ were 500 miles away. She correctly described a large tree with a slope behind it. She also noted that Puthoff was clowning around in the tree in a “very unscientific” manner. In fact, he had climbed around the branches of the tree. Swann followed next and was just as correct with the target he described – the atrium of a busy shopping mall.

Both viewers should have done a total of 4 dives, but the Taurus changed its operational plans and so the researchers had to be content with what they had so far. But these were remarkable and an important milestone in research. At first it was clear that ELF could also be excluded as a transmission route. However, this also meant that the entire electromagnetic wave spectrum was ruled out for the explanation of PSI perception. This in turn led to dramatic conclusions: Apparently there was no known physical way to shield any target from the eyes of a remote viewer. This fact, which was to become very interesting for intelligence agencies in the future, meant at the same time the exclusion of Remote Viewing from mainstream science. Since the phenomenon of PSI perception could not be explained with physical means, it did not fit into the scientific worldview. What science could not explain was dropped as “unscientific”.

This experiment and its results played a central role in the history of remote viewing. So Hella holds at least three titles: first female remote viewer, first “normal person” viewer without prior psychic experience, first ARV session.

Excerpt from the report of the 4 Grill-Flame visitors at the SRI 1979

With Stephan A. Schwartz, Hella Hammid later had a total of 15 years of collaboration and 9 expeditions. The “Alexandria Project” is certainly the best-known major project of that time, as is the search for the Brig Leander, the shipwreck. For this work the term “ psychic archeology” was coined.

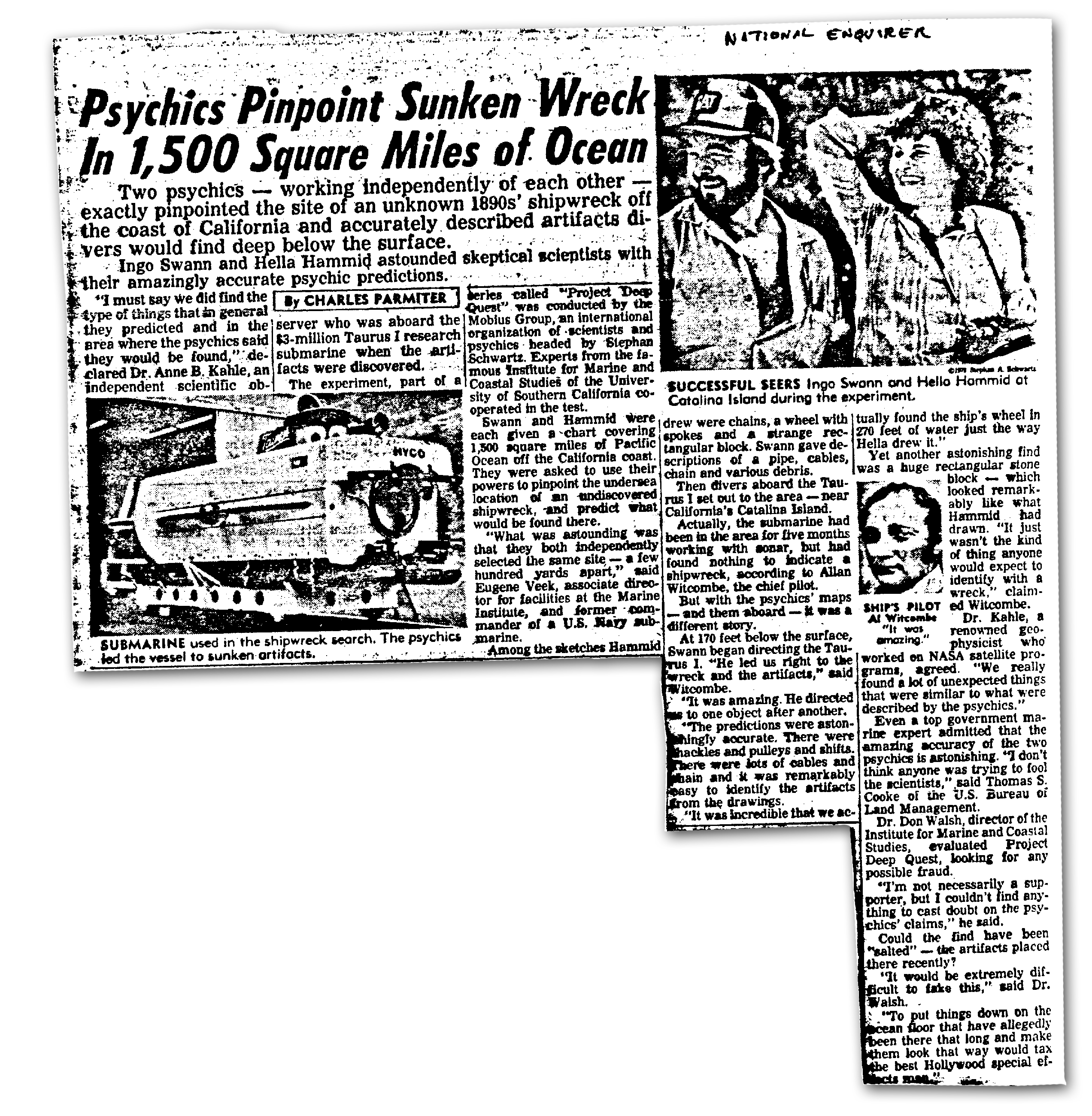

A newspaper article from 1977 reports on the first part of the “Deep Quest” experiment and the “Mobius laboratory” by Stephan A. Schwartz. Seven remote viewers, including Ingo Swann, Hella Hammid and the well-known clairvoyant Alan Vaughn, were asked to locate a shipwreck that was suspected to be on the seabed off the California coast. In fact, the viewers determined a location with relative agreement, and the research submersible “Taurus I” found the remains at the location described.

A newspaper article from 1977 reports on the first part of the “Deep Quest” experiment and the “Mobius laboratory” by Stephan A. Schwartz. Seven remote viewers, including Ingo Swann, Hella Hammid and the well-known clairvoyant Alan Vaughn, were asked to locate a shipwreck that was suspected to be on the seabed off the California coast. In fact, the viewers determined a location with relative agreement, and the research submersible “Taurus I” found the remains at the location described.

The Case of ESP – Original, Uncut 1983 BBC Film

(04.12.2013)